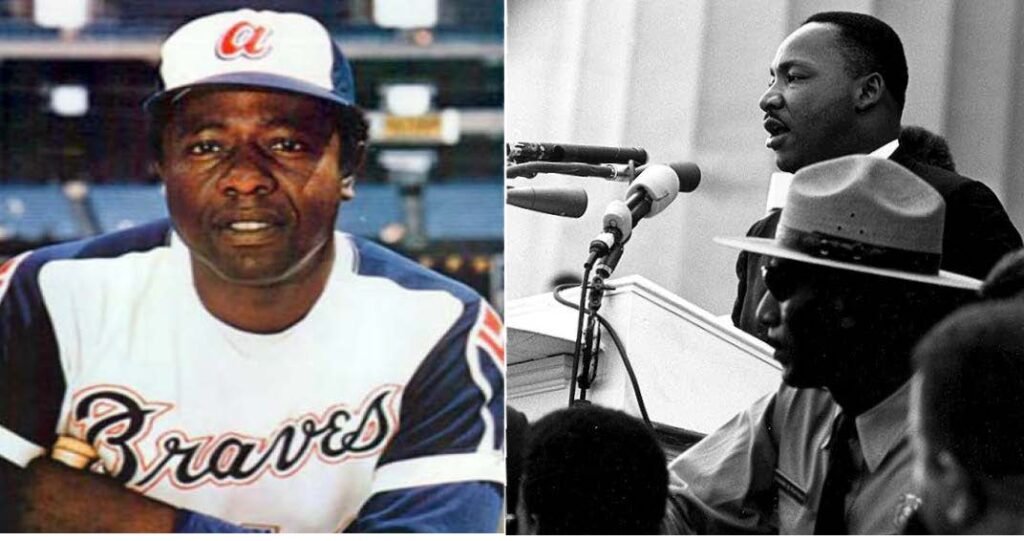

Hank Aaron, an all-time baseball great, was hesitant to move to Atlanta from Milwaukee with the Braves because of his experiences growing up in segregated Mobile, Alabama and as a minor leaguer in Georgia. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was among those who encouraged Aaron to play in Atlanta.

Yesterday was the 60th anniversary of the ending of the 72-day filibuster in the United States Senate that had blocked passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Within a month President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which opened and transformed American society. This week’s Justice Blog focuses on a little-discussed impact of the Act, the introduction of major league sports franchises to the Deep South.

Anybody who has spent appreciable time around me knows that I am passionate about civil rights and sports. In the quarter century after World War II, there was a close intertwining between civil rights progress and sports. About Jackie Robinson, who integrated Major League Baseball in 1947, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said the following:

Jackie Robinson made it possible for me in the first place. Without him, I would never have been able to do what I did.

The founder of the civil-rights movement was Jackie Robinson.

As far as I can tell, nobody has written the definitive book about civil rights and sports covering the decades after World War II. When somebody does, I will be among the first to buy it. Today’s blog discusses one piece of that history.

It is difficult for a city in America to be considered a major city unless it has a major league sports franchise. It is the reason why cities spent exorbitant amounts of money investing in major league franchises to obtain and retain them. In recent decades, cities like Nashville and Columbus have aggressively sought professional teams to elevate their status, whereas Oakland is going through an existential crisis as after this year, the Oakland Raiders, Golden State Warriors, and Oakland Athletics will all have left the city in five years.

The late 1950s and the 1960s were an extraordinary period of expansion for major leagues sports both in terms of numbers of teams and geographically. Major League Baseball went from sixteen to twenty teams. In football, the American Football League started in 1960 to rival the National Football League, and in response, the NFL added teams. In 1957, California had two major league teams, both in the NFL. By 1962, it had three MLB teams, two NFL teams, two AFL teams, and two teams in the National Basketball Association.

There was one region in the country where there were no major league sports teams – the Deep South. The primary reason why; it was no longer acceptable to have a professional sports team in a formally segregated society.

The closest teams were in Texas, where four major league sports teams were formed between 1960 and 1962: the Dallas Cowboys (NFL), the Dallas Texans (AFL), the Houston Oilers (AFL), and Houston Colt 45s (MLB). Part of the tradeoff of having those teams was that public accommodations would need to be desegregated. The Astrodome and Desegregation discusses how this happened with the Colt 45s (later renamed the Astros after the Houston Astrodome was built):

Originally named the Colt .45s, the addition of an integrated baseball team playing in a world-class integrated facility brought more opportunity for the dismantling of Jim Crow in Houston. [Black community leader Quentin] Mease and [Colt 45s owner Judge Roy] Hofheinz recognized that when black athletes visited the city to play ball, they would also require sleeping, dining, and entertainment accommodations. . . . [H]otels throughout the area repealed their segregation policies on April 1, 1962. Realizing that maintaining segregationist practices under national attention would be bad for sales, other local business owners quickly followed suit. And when the Colt .45s played their first game in the temporary stadium a few weeks later, Hofheinz proudly boasted that the Houston Sports Association had successfully championed for a fully integrated experience; without any national or federal pressure or backlash from white citizens of Harris County.

The Deep South presented greater challenges. The University of Pittsburgh and Georgia Tech University were chosen to play in the 1956 Sugar Bowl, a prestigious college football bowl game in New Orleans. The University of Pittsburgh had a black player, Bobby Grier, and the university insisted he participate in the game. Georgia Tech had played integrated teams before but never in the Deep South. Georgia’s Governor sent the following telegram to the university Board of Regents.

The South stands at Armageddon. The battle is joined. We cannot make the slightest concession to the enemy in this dark and lamentable hour of struggle. There is no more difference in compromising integrity of race on the playing field than in doing so in the classrooms. One break in the dike and the relentless enemy will rush in and destroy us.

Georgia Tech’s President said he would resign if the regents did not allow the team to play. The regents voted 13-1 to play and the game went forward.

But this was not the end. Later, in 1956, Louisiana enacted Act 579 which:

prohibited “interracial activities involving personal and social contacts”, including “games, sports or contests”, and require[d] separate seating at any entertainment or athletic contest.

In Georgia, the President of Georgia Tech died within a month of the 1956 Sugar Bowl. In 1957, Leon Butts, a one-term Georgia State Senator, introduced a bill similar to Act 579 in Georgia. One of Butts’ stated targets was professional baseball – he said that some of his constituents refused to go to minor league baseball games involving white and Black players. His bill passed the Georgia Senate unanimously, but the legislative session ended before the Georgia House voted. Disappointingly, in 2017, the Georgia House passed a resolution honoring Senator Butts that noted his “diligent[] and conscientious[]” service in the State Senate.

Contrary to Senator Butts, there were others that wanted to bring both major legal sports to the state. Atlanta had ambitious business leadership. The 1961 Atlanta mayoral election was an inflection point – the candidates were Atlanta Chamber of Commerce President Ivan Allen Jr. vs. avowed segregationist Lester Maddox. Allen won the election with the Black vote being decisive.

Allen had campaigned on building a modern stadium that would attract a major league team. He went to work on that and on talking to major league baseball owners. But no major league team could move to a segregated city. On the day he took office in early 1962, he desegregated city government.

Meanwhile, Congress was working on legislation that would bar discrimination in public accommodations. Mayor Allen was the only elected state and local elected official from the South who testified in favor of such legislation. In his July 1963 testimony before the Senate, he not only detailed the experience in Atlanta and made the compelling case for integrated accommodations, but he stood up to extended questioning from segregationist Senator Strom Thurmond.

The next year Congress would enact the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title II included a strong public accommodation anti-discrimination provision. Section (a) sets forth the general standard:

All persons shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, and accommodations of any place of public accommodation, as defined in this section, without discrimination on the ground of race, color, religion, or national origin.

Section (b) defines what facilities are public accommodations and the list is extensive.

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 opened major league sports to the Deep South. The Milwaukee Braves moved their baseball team to Atlanta in 1966 to play in brand new Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. The NFL granted Atlanta an expansion team that began playing in the same stadium later that year. Atlanta had its third major league sports team when the NBA’s St. Louis team moved to Atlanta in 1968. The expansion went beyond Atlanta as expansion professional football teams began play in Miami in 1966 and New Orleans in 1967.

Two postscripts. First the battle between the “old South” and “new South” did not end with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It entered a new phase. Lester Maddox refused to make his Atlanta restaurant available to Black customers. When he was sued under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he lost. He responded by closing the restaurant. Then he ran for Governor in 1966. And won. Georgia law prevented him from running for Governor in 1970 so he ran for Lieutenant Governor. And won again. But he served under a Governor who epitomized the New South, Jimmy Carter, who would become President six years later.

Second, Hank Aaron is an all-time baseball great who spent almost his entire career with the Braves. His biographer Howard Bryant wrote a story for ESPN where civil rights leader and UN ambassador Andrew Young related to Bryant that Aaron was hesitant to move from Milwaukee to Atlanta. Aaron had not only grown up in segregated Mobile, Alabama but had an awful experience in Georgia as a minor league player. Atlanta resident Dr. King helped persuade Aaron to move to Atlanta.

Aaron would break the major league home run record in 1974 for Atlanta. Legendary broadcaster Vin Scully captured the moment perfectly:

What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.

In the same ESPN article, Ambassador Young and President Carter described the importance of professional sports to the Atlanta and the South:

Ambassador Young:

People always talk about the marches and the protests, but what they don’t talk about is how big a part sports played in the economic part of the movement, in changing the perception of what the South was. We had no professional sports teams, and the mayor, Ivan Allen, believed attracting pro sports and big pro events would be critical to proving to business leaders around the country that we did believe in a ‘new South.’

President Carter:

Having sports teams legitimized us. It gave us the opportunity to be known for something that was not going to be a national embarrassment. Henry Aaron was a big part of that because he integrated pro sports in the Deep South, which was no small thing. He was the first black man that white fans in the South cheered for.