The “three wise monkeys” were created in the 16th Century from a shrine in Japan but the underlying of maxim of “hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil” for somebody who is trying to avoid the truth goes back more than 2,000 years to China, at least according to Wikipedia.

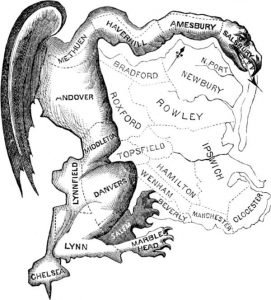

When one political party controls the redistricting process in a state, its aim often is to further partisan interests. This is not difficult to understand – it is self-interest. The term gerrymander is named after Elbridge Gerry, the governor of Massachusetts, who signed a Massachusetts redistricting bill in 1812 that featured an oddly shaped district designed to elect more Democrat-Republicans state senators at the expense of Federalist incumbents.

This is a political cartoon published in the Boston Gazette of the original “gerrymander.”

The Supreme Court punted for decades as to whether a partisan gerrymander could violate the Constitution, with Justice Kennedy’s indecision leaving the issue in limbo. After he retired, his replacement, Justice Kavanaugh, cast the deciding vote in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), where the Court held that the Constitution does not recognize partisan gerrymandering claims. I will write about the problems with this decision in the future.

Anybody engaged in redistricting in any jurisdiction with a substantial population of people of color knows the importance of race to redistricting. This is especially true with Black voters, who for decades have voted consistently voted 95-100% for Democrats. In most Southern states, the percentage of Black voters in the district usually determines what type of candidate will be in the seat. Above a certain percentage, usually a Black Democrat. Just below that, a Democrat of any race. Below that, a competitive seat, of which there are typically few. Below that, a Republican, who is almost always white. In one case I litigated at the Department of Justice in the early 2000s I was talking to a Democratic political operative who is now a prominent local elected official. He told me that if a seat was 45% or more Black in population, the party in his state sought a Black candidate; if the seat 30-45% Black, the party sought a white candidate; and if the seat was under 30% Black, it did not matter because a Republican was going to win. Republicans are just as knowledgeable. In a case I litigated in Georgia last decade, a Republican political operative who worked in the State’s Reapportionment Office sent charts and emails to Republican legislators and outside political observers discussing the correlation between the racial demographics of districts and which party held the seats: above 40% Black, a Democrat; between 30-40% Black, a swing seat; below 30% Black, a Republican. He also accurately predicted that Gwinnett County, a suburb of Atlanta, was going to flip from Republican to Democrat because of racial demographic change.

So in areas with appreciable populations of people of color, racial demographics are at the center of the redistricting process. And the issue of discrimination in redistricting has been hotly contested in the last few decades. Last term, the Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision reaffirmed the vitality of vote dilution results claims under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act in Allen v. Milligan (2023). Milligan successfully challenged Alabama’s refusal to draw a second Black-majority (out of seven) Congressional district. The result in Alabama is that the state will likely have two Black members of Congress ever. Beyond Alabama, voting rights attorneys like me breathed a huge sigh of relief because we were afraid the Court would use the Milligan case as an opportunity to weaken or effectively dismantle Section 2 vote dilution cases. That being said, Section 2 cases have pretty rigorous standards beginning with the requirement that the racial/ethnic voters bringing the challenge have to show that the racial/ethnic group is large enough to constitute a majority in the district they are challenging.

The Supreme Court giveth last term. This term, they taketh away. Last Thursday, in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, the Supreme Court held that plaintiffs cannot prevail in a racial gerrymandering case (Footnote) when they cannot prove that racial motivations predominated over partisan motivations when the map drawers raise a partisan defense. Much of the argument in Alexander focused on whether the lower court had properly found that racial motivations had predominated over partisan motivations. My point is that the race vs. partisanship argument is a false dichotomy because frequently redistricting is about the connection between race and partisanship. Map drawers often use race to achieve a partisan result. They are moving Black voters and other voters of color around to achieve partisan ends.

Alexander provides an excellent illustration about how race and partisanship work together and why this should be considered discrimination. I am drawing largely from the facts in the lower court opinion. The case involved a challenge to South Carolina’s First Congressional District. This district has traditionally contained portions of Charleston County and surrounding counties. Under the post-2010 Census redistricting plan, this was South Carolina’s most competitive district, mostly electing Republicans but electing a Democrat for one term in 2018. The 2018 and 2020 elections were each decided by less than one percentage point. At the time of the post-2020 redistricting and currently, it is represented by Republican Nancy Mace.

Because of the one-person, one-vote standard (which for Congress requires that each district have almost identical populations), District 1 and every other district would have to be redistricted after the 2020 Census. District 1 had an excess population of 87,689. In other words, if no population was added to District 1 almost 88,000 people would have to be moved out of District 1. The South Carolina General Assembly, which was controlled by Republicans, had several aims. They wanted to make the District more Republican; they wanted to move the remainder of two counties, Beaufort and Berkeley into District 1; they wanted to move a significant portion of a Dorchester County into District 1; and they wanted to reduce the Black population of District 1 to 17%. Analysis had shown that a Black population of 17% would tilt the district Republican; a Black population of 20-23% would make the district competitive; and a Black population of over 23% would tilt the district Democratic. Accomplishing all of these goals was challenging especially given that the portions of Beaufort, Berkeley, and Dorchester Counties in District 1 was 544,521 of the ideal population of 731,203 and the Black percentage was 20.3%. The only way for map drawers to achieve their objective was to take a lot of Black people from Charleston County out of District 1. They moved 62% (30,243 out of 48,706) of the Black population in Charleston County that had previously been in District 1 to adjoining District 6. At the same time, the map drawers were claiming that this plan was a “least change” plan.

In Justice Alito’s majority opinion in Alexander, he uses the fact that race and partisanship are highly correlated against the plaintiffs. Indeed, I think the words correlate, correlated, or correlation show up eight times in a thirty-five page opinion. In sum, he says partisan gerrymandering is constitutionally acceptable and everything plaintiffs bring forward as proof of racial gerrymandering (that he does not otherwise reject), he can just as easily show is partisan gerrymandering. He cites to the fact that the map drawer was focused on the partisan composition of District 1, not its racial composition, when making changes to the district. Post-Rucho, this is a favorite tactic of map drawers. Do not look at the racial demographics in the map drawing software, only the partisan projections. But as this map drawer and anybody else that knows anything about politics in the South knows, the best way to change partisan composition is to change racial composition. So when the changes to maps dramatically change the partisan performance numbers, it is usually because the racial composition has changed, especially in the South.

The majority makes a big deal that the plaintiffs failed to produce an alternative map showing that that the map drawers could have achieved the same partisan result with a different racial composition. I find this totally illogical. Why should it be okay when the only way to achieve a partisan result is through racial manipulation? How does the partisan motivation excuse racial discrimination?

I simply do not get it. In my view, see no evil, speak no evil, hear no evil. The conservative majority who takes great offense in cases like Shaw v. Reno (see footnote) where Black voters were moved around so that Black people could get elected to Congress from North Carolina for the first time in more than 90 years are unbothered when Black people are moved around to make a congressional district more Republican. In Chief Justice Roberts’ first term on a Court, he said in LULAC v. Perry (2006), a redistricting case: “It is a sordid business, this divvying us up by race.” Apparently, the divvying up by race is not sordid to him when it is done for partisan reasons.

Another way of putting it is when it comes to redistricting the court is saying is if the end is legitimate, it does not matter whether the means are not. I did not have to look far to find an example in a different context where the Court found otherwise. This is what Justice Gorsuch said on behalf of six-member majority in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia: “Intentionally burning down a neighbor’s house is arson, even if the perpetrator’s ultimate intention (or motivation) is only to improve the view.”

To be fair to the Supreme Court, the South, and Republican legislators, my colleagues and I lost a similar case for similar reasons in a lower court, involving Illinois State House redistricting, and Democratic legislators. We did not appeal out of concern that the Supreme Court would do what it did in Alexander. The result in Illinois was catastrophic and reading the decision again in writing this piece reignited my anger. To me, it also illustrates what is wrong with the Court’s decision in Alexander.

East St. Louis, Illinois is right across the border from St. Louis, Missouri. It is 95% Black. It is one of the most impoverished cities in the country and its Black people have experienced a long history of discrimination. One resource the people of East St. Louis had from the mid-1970s until 2022 was a Black member from East St. Louis in the Illinois State House. In the post-2020 Census Illinois redistricting, Democrats had full control. If you looked at the partisan composition of the State House at the time of that redistricting, there were three blue seats in a sea of red in the western part of Illinois. These Democrats all represented an area known as Metro East. District 114 was the seat representing East St. Louis and adjoining areas and was represented by LaToya Greenwood, the only Black House member in that area of the State. Adjacent to District 114 to the north and east was District 113 represented by white Democrat Jay Hoffman. With Black people moving from East St. Louis to the north and east and reasonable support from white voters, Hoffman’s received no less than 59% of the vote in the 2012-2020 election, peaking at 75% of the vote in 2020. District 112 was to the north and east of District 113. Between 2010 and 2020, more Black people gradually moved into the district. White Democrat Katie Stuart had flipped the seat in 2016 and won the two successive elections relatively narrowly.

In the post-2020 Census redistricting, the Democrats wanted to shore up Katie Stuart’s seat while not compromising Jay Hoffman’s. How did they do it? They moved Black people into District 112, mostly from District 113. Because District 112 started out overpopulated, they had to move out a lot of white people. To keep Hoffman’s district relatively safe, they replaced the Black people that moved to District 112 by moving Black people out of District 114 and into District 113. District 114 had started out underpopulated and to equalize population they had to move a lot of white people into the district, which made it vulnerable. Our analysis showed it as a toss up district in 2022 with it moving increasingly Republican over time.

In defending the lawsuit, the Democrats originally disclaimed that they did not pay to attention to race at all. At the hearing in the case, they admitted that they manipulated the racial demographics for the benefit of the white Democrats. We thought this should be victory for us and one of our lawyers even said as much at the hearing. Not so fast. The court found that because “it does not appear there was any other viable way to protect the Metro East Democrats,” manipulating the racial composition of the districts was constitutional. In other words, the discrimination was excused because it was the only way to achieve the desired partisan result.

So what happened in the 2022 election. Katie Stuart won District 112 with 54.2 % of the vote, Jay Hoffman won District 113 with 59.5% of the vote, and LaToya Greenwood lost District 114 with 47.2% of the vote. East St. Louis, one of the Blackest and poorest cities in the country, is now represented in the Illinois State House by a white Republican who was not their candidate of choice.

Footnote: As people who I have worked with me know, I am not big on footnotes. I am using one here to explain various terms. “Vote dilution” means that one person’s vote is improperly worth less than another’s. The simplest example is a blatant one person, one vote violation. A state elects its State House by having each county elect one member. Under such circumstances, a person living in a county of 1 million people has less substantially less voting power than the person living in a county of 1,000. The concept of “minority vote dilution” came into vogue after Southern states could not prevent Black people from voting and instead developed ways to minimize the Black vote. One way was “crack” a Black community into multiple districts to prevent Black votes from electing their candidate of choice. Another was to “pack” a large Black population into as few districts as possible. Minority vote dilution can be brought on intentional and/or results theories.

“Racial gerrymandering” clams, otherwise known as Shaw claims, because of the case where the Court first recognized the claim, Shaw v. Reno (1993), originally served as a claim conservative justices recognized in challenges brought by white voters to oddly-drawn districts used to create Black-majority districts after the 1990 Census. But they are not white vote dilution cases, and the Court has made clear from the beginning, and reiterated in Alexander, that racial gerrymandering claims are “analytically distinct” from vote dilution claims. In Shaw, the harm the Court identified was a stigmatic harm, presumably mostly to black people: “A reapportionment plan that includes in one district individuals who belong to the same race, but who are otherwise widely separated by geographical and political boundaries, and who may have little in common with one another but the color of their skin, bears an uncomfortable resemblance to political apartheid.” In a future post, I will discuss the Court’s history of the doctrine and the issues I have with the Court in greater detail.